With the major league baseball season now underway, I was interested to read that all of baseball’s Triple-A teams – that’s the highest-level league before the majors – will be using an electronic strike zone. (It was used in some games last season, and has been in operation in a number of lower-level leagues since 2019. The pandemic has somewhat delayed implementation.)

The Automatic Balls and Strikes system, commonly referred to as ABS, will be deployed in two different ways. Half of the Class AAA games will be played with all of the calls determined by an electronic strike zone, and the other half will be played with an ABS challenge system similar to that used in professional tennis.

Each team will be allowed three challenges per game, with teams retaining challenges in cases when they are proved correct. [Major League Baseball’s] intention is to use the data and feedback from both systems, over the full slate of games, to inform future choices. (Source: ESPN)

ABS is composed of these four subsystems:

- The MLB tracking system

- An interface the ballpark operator uses to set the correct batter

- An MLB server that receives the tracking data and has the ball-strike evaluation code

- A low-latency communication system to relay calls to the umpire

And here’s how it works:

The primary inputs for ABS are the pitch arc — the path the ball takes as it proceeds from the pitcher to the catcher — and the location and dimensions of the strike zone. The pitch data generated by the MLB tracking system is composed of a set of polynomials describing the path the center of the ball travels through space in MLB’s standard coordinate system, where the y-axis points toward the pitcher’s mound from the back of home plate, the z-axis points directly up from the back of home plate, and the x-axis is orthogonal to the other two axes.

As soon as the pitch data has been generated by the tracking system, ABS uses that information and the current strike zone definition to determine whether the pitch is a strike. The strike zone definition has varied across different iterations of the ABS system, but as a general rule, ABS constructs a two-dimensional shape on the x/z plane at a specific depth and checks whether the ball intersects that shape. The ball is modeled as a circle centered at a point along the pitch arc with a radius of 1.45 inches as defined in Rule 3.01 of the Major League Rulebook. The result of the ball/strike evaluation is then relayed to the umpire. (Source: MLB Technology Blog)

The results so far have proved to be very accurate and timely.

By the way, the umpire will not be standing around waiting for the result to get there. (If you follow baseball at all, you’ll be aware that speeding up the game is a big issue, so MLB will be doing nothing to slow things down.) From the broadcast graphics of the strike zone that are used in most MLB broadcasts, they’ve learned that those graphics are faster with their updates than the umpire is making their call. This provides a window of opportunity for ABS to inform the umpire of the call, letting them know whether to use their right hand (strike) or left hand (ball).

It’s also important to note that the umpire does retain some autonomy, and will utilize their own judgement when matters that aren’t limited to the strike zone occur: checked swings, catcher interference. Also, if there’s too much latency, the umpire will go ahead and call the pitch. (Again: no one wants to delay the game!)

There’s a lot more detail in the MLB Technology Blog, if you’re interested.

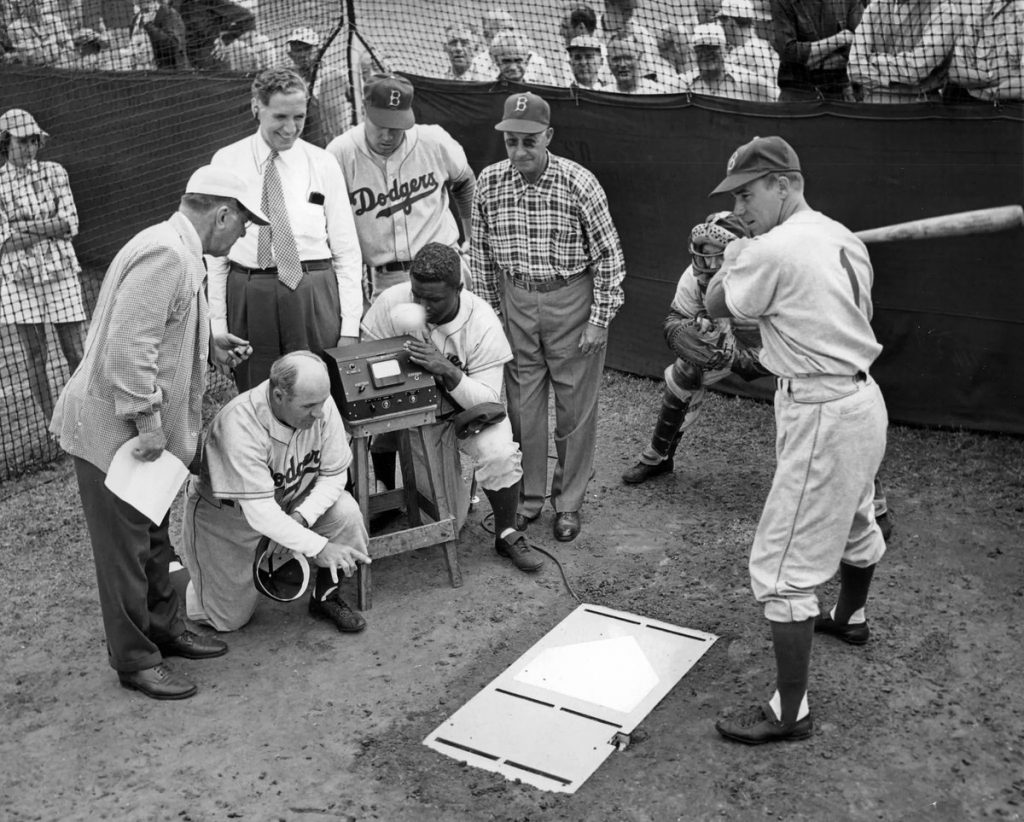

Meanwhile, in reading about automation coming to baseball umpiring, I came across an article about an attempt at automated umpiring that happened in March 1950 at the spring training facility for the Dodgers – at that time, the Brooklyn Dodgers.

The so-called “cross-eyed electronic umpire” introduced that day used mirrors, lenses and photoelectric cells beneath home plate that would, after detecting a strike through three slots around the plate, emit

electric impulses that illuminated what The Brooklyn Eagle called a “saucy red eye” in a nearby cabinet.

Popular Science declared, “Here’s an umpire even a Dodger can’t talk back to.”…

“It was definitely a novel use of existing technology, using a photoelectric cell to size the strike zone,” he[Mike Jakob, the president of Sportvision] said. “But,” he added, “it couldn’t be used for night games.” (Source: New York Times)

Branch Rickey, president and part-owner of the Dodgers, was a visionary, but he wasn’t envisioning automated umpiring. He was planning on using the machine as a teaching tool to help pitchers learn how to perfect their bunting technique. (That 1950 machine, incidentally, was created by a General Electric team located in Syracuse. Team leader Richard Shea “specialized in semiconductors, did the initial circuit design work for the company’s first transistors and also worked at Knolls Atomic Power Laboratory.” Even without the invention of the automated umpire, that’s some resume!

Anyway, if Major League Baseball in 2023 is not quite ready to automate baseball umpiring, they sure weren’t in 1950!

Meanwhile, Syracuse has a AAA club – The Mets – so I may actually see ABS in person this summer. It’ll be interesting to see how it changes the dynamics of the game. Play ball!

electric impulses that illuminated what The Brooklyn Eagle called a “saucy red eye” in a nearby cabinet.

electric impulses that illuminated what The Brooklyn Eagle called a “saucy red eye” in a nearby cabinet.