There’s been no escaping the news about the drastic heat being experienced throughout the Southwest and the South this summer. And if you live in those regions, there’s been no escaping heat that’s been well above 100 degrees for days, even weeks, at a time. We don’t have heat like that in Central New York. At least not yet. We do typically have a number of 90+ days, and that number has been creeping up.

The last few summers have been hotter than average in Central New York with 15, 18, and 21 90+ degree days in the summer of 2022, 2021 and 2020, respectively. Remember, the average number of 90+ degree days in Syracuse each year is 10 over the last 30+ years. (Source: LocalSYR.com)

But 100+ days remain a rarity. At least for now.

I can only imagine how difficult it must be to live and work in that kind of heat.

As the earth continues to heat up, most scientists predict that there’ll be more and more of what would have once been considered weather anomalies – the new normal will be abnormal.

The good news is that there are many technologists focusing on ways to remediate the effects of global warming.

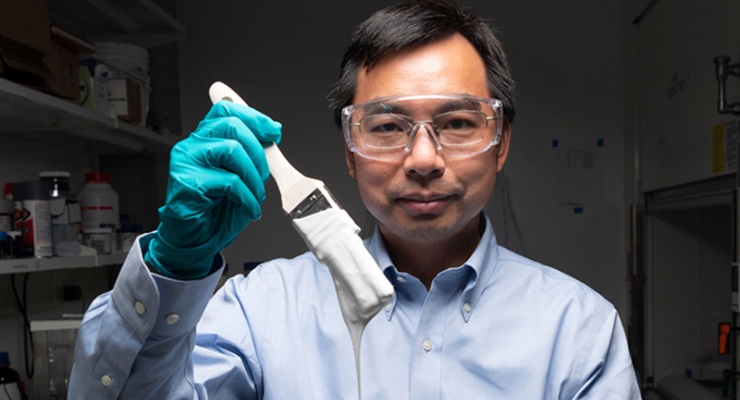

One such technologist is a Purdue University professor of mechanical engineering Xiulin Ruan, who has been working for years to develop a white paint that can cool buildings down without the side effects produced by a massive use traditional air conditioning.

In 2020, Dr. Ruan and his team unveiled their creation: a type of white paint that can act as a reflector, bouncing 95 percent of the sun’s rays away from the Earth’s surface, up through the atmosphere and into deep space. A few months later, they announced an even more potent formulation that increased sunlight reflection to 98 percent.

The paint’s properties are almost superheroic. It can make surfaces as much as eight degrees Fahrenheit cooler than ambient air temperatures at midday, and up to 19 degrees cooler at night, reducing

temperatures inside buildings and decreasing air-conditioning needs by as much as 40 percent. It is cool to the touch, even under a blazing sun, Dr. Ruan said. Unlike air-conditioners, the paint doesn’t need any energy to work, and it doesn’t warm the outside air. (Source: NY Times)

The paint was developed with rooftops in mind, but there are other applications in the making. E.g., a “more lightweight version that could reflect heat from vehicles.”

I’m always delighted to see my fellow engineers getting in on the act of improving life here on earth. One is Jeremy Munday, who is a professor of electrical and computer engineering at UCal-Davis.

He calculated that if materials such as Purdue’s ultra-white paint were to coat between 1 percent and 2 percent of the Earth’s surface, slightly more than half the size of the Sahara, the planet would no longer absorb more heat than it was emitting, and global temperatures would stop rising.

This would not, of course, be as simple as white-topping half the Sahara Desert. It would have to be spread across many settings in many regions, with checks in place to make sure that weather disruptions and other unintended consequences aren’t introduced.

The Purdue white paint, which should be available commercially next year sometime, is not a panacea. The challenge is a complex one, with many intertwined economic, political, geopolitical, environmental, and cultural implications. And it’s not going to be solved overnight.

Nonetheless:

Large-scale radiative cooling, Dr. Munday said, would be akin to a life raft.

“This is definitely not a long-term solution to the climate problem,” Dr. Munday said. “This is something you can do short term to mitigate worse problems while trying to get everything under control.”

Meanwhile, one of the unintended consequences of Xiulin Ruan’s work was that, in 2021, Guinness named the Purdue ultra-white page “the whitest paint ever.”

Guinness Book of World Records aside, it’s good to see that solutions are being developed that will help “get everything under control” and give Mother Earth some more breathing room. So I’m all for the Purdue paint, hoping that it produces a new and different white coat effect.

temperatures inside buildings and decreasing air-conditioning needs by as much as 40 percent. It is cool to the touch, even under a blazing sun, Dr. Ruan said. Unlike air-conditioners, the paint doesn’t need any energy to work, and it doesn’t warm the outside air. (Source:

temperatures inside buildings and decreasing air-conditioning needs by as much as 40 percent. It is cool to the touch, even under a blazing sun, Dr. Ruan said. Unlike air-conditioners, the paint doesn’t need any energy to work, and it doesn’t warm the outside air. (Source: