As we’re nearing that great time of year when local farm stands (and neighbors’ backyard gardens) have local tomatoes, I couldn’t resist what appears to be an advertorial by Analog Devices (a.k.a. ADI) that appeared in a recent Technology Review. I mean, how could I pass up a piece entitled IoT: The Internet of Tomatoes?

ADI is headquartered in Massachusetts, and the piece starts out with a critique of New England native tomatoes. I went to grad school in Massachusetts, and I don’t recall the native tomatoes being awful, but I’ll take ADI’s word for New England’s tomatoes being “comparatively tasteless” fare that generally get turned into ketchup rather than get served up in a nice Caprese sandwich. Anyway, ADI partnered with some local farmers on their Internet of Tomatoes project.

“This precision agriculture experiment uses technologies such as micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) and sensors to figure out whether environmental monitoring could improve flavor.”

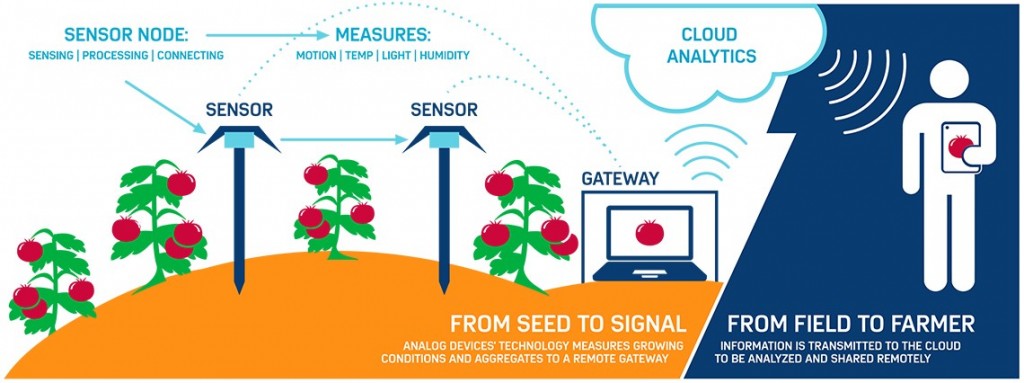

It looks at two aspects of tomato-cultivation: temperature and “growing-degree days.” Their launch was in January. Having been in Massachusetts in January (not to mention having spent my life in Upstate New York), I can promise you that there’s not a lot of farming going on. But January 2015 – that was the year New England really got clobbered with a ton of snow – would have made a good test case for technology survival. Working on a farm that lacked both usable power and Internet access, they decided on wireless (Bluetooth) sensors that communicate with handhelds (iOS or Droid). Data being communicated includes average daily max and min temperatures that are specific to each farm. The system is also incorporating info from a pest-management application, so farmers can keep tabs on beetles. Overall, the goal is to figure out best to cultivate tomatoes, and the best time to harvest them.

ADI is also taking a look at the chemistry of tomatoes. In doing so they’ve figured out why New England tomatoes aren’t as tasty as those found elsewhere:

“They don’t have high fructose, glucose, or salt content—which is why when most people grab a New England–grown tomato, they also grab a salt shaker…From an aesthetic perspective, the New England tomatoes look like any other. But on the inside, the chemistry doesn’t match up, according to ADI’s analysis of thousands of tomatoes.”

ADI is also experimenting with a non-invasive way to test tomato chemistry, not just for taste but for nutritional value. They’re working on an optical system that uses nearfield infrared technology. “Optical technology will [also] measure the soil, leaf, and stem lengths and their stress levels.”

Overall, it looks like an excellent use case for the IoT.

But about those salt shakers: I was of the belief that part of the pleasure of eating a native, Upstate New York tomato is having the tomato in one hand and the salt shaker in the other. Given this, I’m guessing that ADI’s Internet of Tomatoes will find a home in my neck of the woods, and not just in New England.